As a woman, it gives me immense satisfaction to honour the achievements of female peers, even if it is as small as being able to dine out alone or successfully complete a workout. For many it might seem trivial or even childish, but it becomes necessary when you are constantly judged, not on your merit but on your gender. While I do support my peers, I decided to look beyond as I came across an article which mentioned about how we conveniently choose to ignore patronage of women in art and architecture. Through research I came across many ‘female’ historical figures who have contributed greatly in developing the art and architectural landscape of India, one of them was Nur Jahan.

We have covered the administrative skills of Mehr-un-Nissa in the last post (see ‘Nur Jahan: A Force to be Reckoned With’), but she was equally brilliant in financial matters of the empire. Excerpts from her life are captured in detail by the Dutch merchant Francisco Pelsaert who mentions that she turned land grants (jagirs) given by Jahangir into commercial success and had her own ships that were used for trade with Persia, Arabia, and Africa. She was also an advocate for vulnerable citizens in need, especially women. Her generosity knew no bounds as she supported the wedding of 500 orphan girls and even designed inexpensive wedding dresses for them. For women in harem, who were between the age of 40 and 70, she offered the choice of either leaving the palace to look for a husband or stay with her. With this decision, she proved that she was ahead of her time as women of harem had never been given a choice in Mughal history.

Aside from her prowess in the matters of empire, she is also known for her love of art and architecture. She used her position to support artists, musicians, and architects. Her love for embroidery is reflected in the clothing that she designed, and it created fashion trends in the Mughal Empire. One of her most famous creations is the Nurmahali dress or the inexpensive wedding dress that she designed for the poverty-stricken young women. Her attention to details is also visible in the buildings that she commissioned. Palsaert mentions that “her refined tastes were also evident in the ‘very expensive buildings’ she erected in all directions—sarais, or halting-places for travellers and merchants, and pleasure-gardens and palaces such as no one has ever made before.”

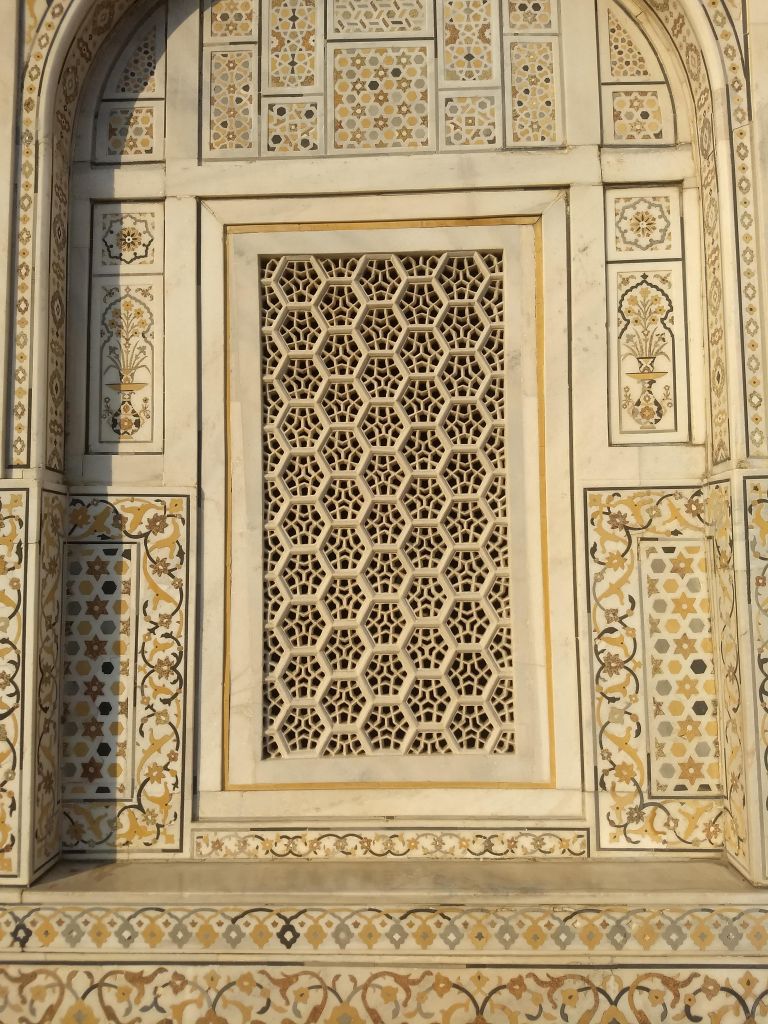

Some of her famous creations are Mughal Gardens of Achabal (in Kashmir), Tomb of her father Itimad-ud-Daula in Agra, and her own tomb in Lahore. Gardens of Achabal have been captured in detail by French physician Francois Bernier who mentions that it had lavish array of fruit trees, fountains, and a man-made waterfall which was illuminated from behind by several lamps. Similarly, the Tomb of Itimad-ud-Daula is an architectural marvel as it took Mughal Architectural style to another level. Intricate details of ornamentation on façade and interiors of the building resembles the art of embroidery that Nur Jahan was fond of.

Apart from these famous monuments, Nur Jahan delved deeply into creating infrastructure for travellers and one of the sarais erected by her still survives in the Jalandhar district of Punjab. The town of Nurmahal derives its name from Nur Jahan who had spent her childhood in this town and was attached to the place. Nurmahal, a part of Phillaur tahsil, is built on the site of an ancient town which was known as Kot Kalur or Kot Kahlur. The town is said to have been ruined by 1300 C.E. In the excavations conducted by Sir Alexander Cunningham, he found coins dating to 12th and 13th centuries, belonging to Satrap and Mahipal period[1]. The town was reconstructed on the orders of Nur Jahan and as it was located on the Grand Trunk Road, on her orders, a sarai was also built here. The task was assigned to Nawab Zakaria Khan, Governor of Doaba, and construction of sarai was completed in 1621 C.E[2]. When Nadir Shah sacked Delhi in 1739 C.E., he ventured in Punjab as well and held Nurmahal captive until a ransom amount of three lakhs were released.

The complex known as Nurmahal Sarai is situated on southern side of the town. It has a square plan with entrance from western and eastern side. Western Gate or Lahori Gate is a triple storeyed structure with red sandstone cladding where the entrance is through a pointed arch. The gateway is known for its grandeur and its façade is dotted with relief panels which have motifs of elephants, riders, fairies, peacocks, lions fighting camels, rhinos, etc. Similar gateway exists on the eastern side as well. Entrance leads to a large courtyard where rooms are located on all sides, a total of 32 rooms on each side with an arched porch, verandah, and alcoves. On north-eastern side of the courtyard, there is a three-bayed mosque with a well. The complex also consists of a Hamam (public-bath) on eastern side of the mosque. There are octagonal bastions on each corner of the complex.

Originally, I had meant to write only one article on Nur Jahan and her contributions, but soon I realised that even two posts are not enough to capture her whole life. Consciously, I have not written anything about her last days because it is a little upsetting for me, and I am aware that I have missed out on a lot but hopefully everyone who is reading this have got a gist of Nur Jahan’s versatility. These posts have made me realize that I need to cover more such stories of figures who are not so popular in mainstream historical narrative, and I will continue to do so.

So, stay tuned for the next posts, till then, happy reading!

[1] Government of Punjab. (1904). Punjab District Gazetteers: Jullundur District. Lahore: Civil and Military Gazette Press, p-297

[2] Dilgeer, D. H. (2004). Encyclopedia of Jalandhar. Belgium: Sikh University Press, p-53

Other Sources:

dazzling! Self-Healing Concrete Could Revolutionize Construction 2025 ornate

LikeLike