As a child, I was aware of only a few places in Patna, mostly because they were our favourite haunts whenever we visited the city. Sanjay Gandhi Biological Park (or the Zoo), Patna Museum, airport, and a few eateries – these were the places I associated the city with. Although I was slightly aware of Patna’s rich antiquity, it became more apparent when I grew up. One of the most important sites that displays the city’s antiquity is situated in Kumhrar.

Kumhrar is a locality that we crossed every time on our visits to Patna for it serves as an entrance to the city while descending from Mahatma Gandhi Setu. I had always related Kumhrar with kumhar (or potter) and had a notion that the place might have something to do with potters; I have never been so wrong. So, before understanding what Kumhrar is about, it is important to familiarize ourselves with a brief history of Patna.

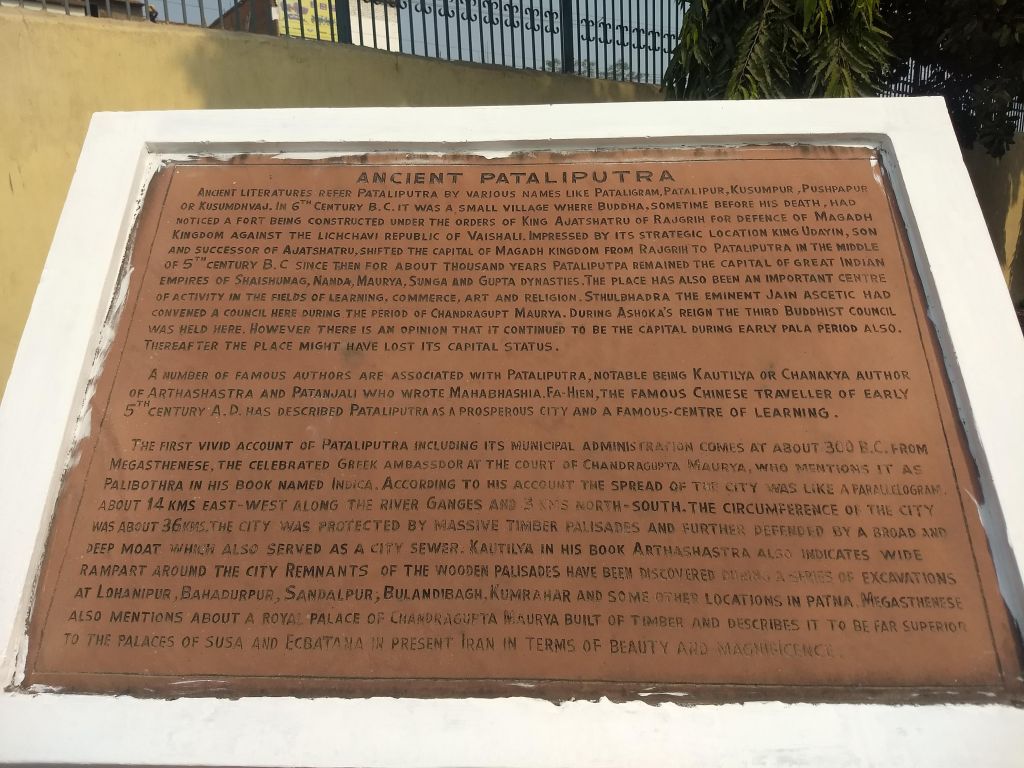

Patna was formerly known as Pataliputra or Patalipattan with history dating back to 600 BCE. It has also been known by various other names such as Kusumpur, Pushpapur, Kusumdwaj, Pataligram, and Azimabad. Pataliputra became the capital of Magadh Kingdom when Raja Udayin Bhadra[1], son of Ajatshatru, shifted his capital from Rajagriha (Rajgir). It seemed as a perfect site for building a capital as it was situated at the confluence of River Ganga and Son. Son River flowed parallel to Ganga, thus resulting in a long stretch of land which was protected from three sides.

After Udayin Bhadra, Pataliputra remained the capital of Magadh during the reign of Nandas, Mauryans, Sungas, and Guptas. During the reign of Chandragupta (323 BCE), Pataliputra become one of the greatest cities in India and its status continued till Gupta Period. Several travelers have written extensively about the city, for e.g. Megasthenes, the Greek Ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya mentions that the city was 9 miles in length and 1.5 miles in width. He has written about the fortifications of the city which was done with massive timber palisades with a deep moat running all around it. There were 64 gates and 570 towers along the fortifications. Fa-Hien, a Chinese pilgrim who visited India in the early 5th Century CE, mentions about the elaborate construction of city, palaces, and its municipal organization. However, by the time Hiuen-Tsang[2] visited Pataliputra in 635 CE, the city was mostly deserted.

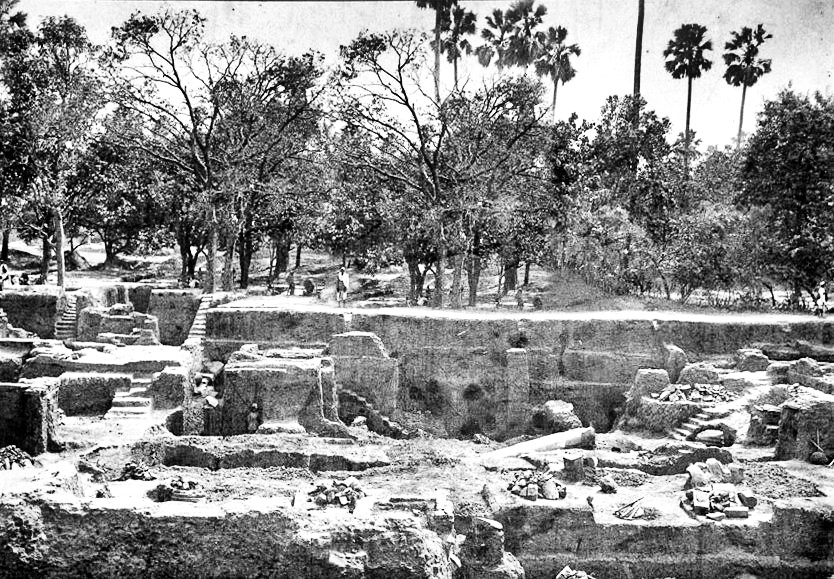

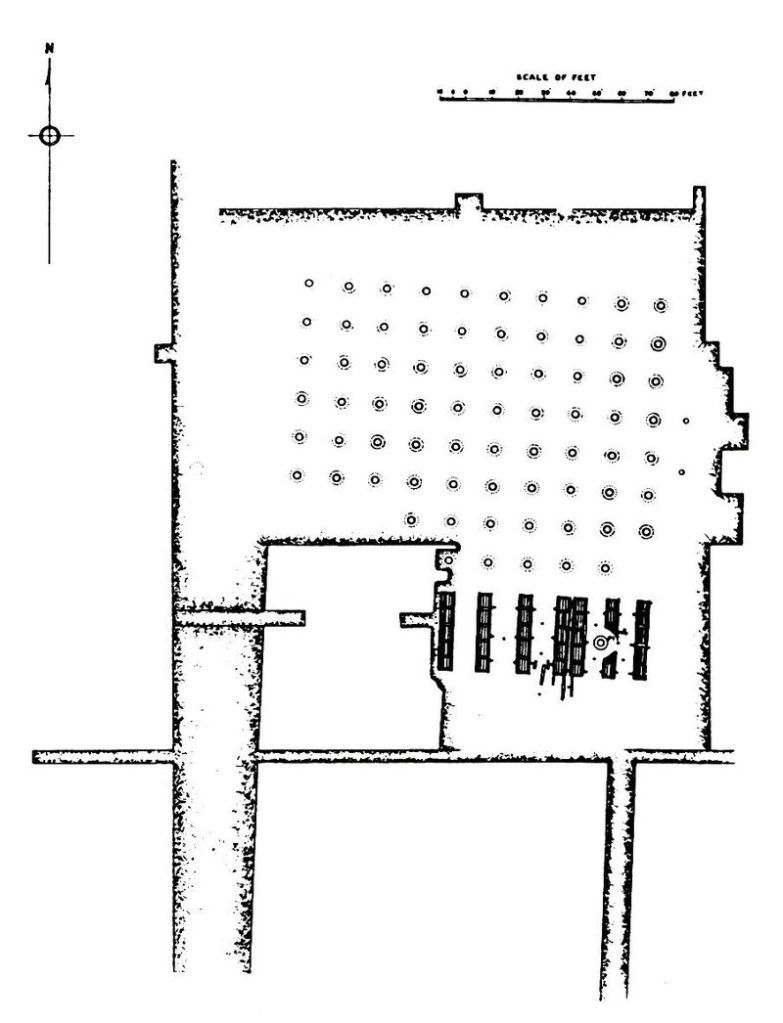

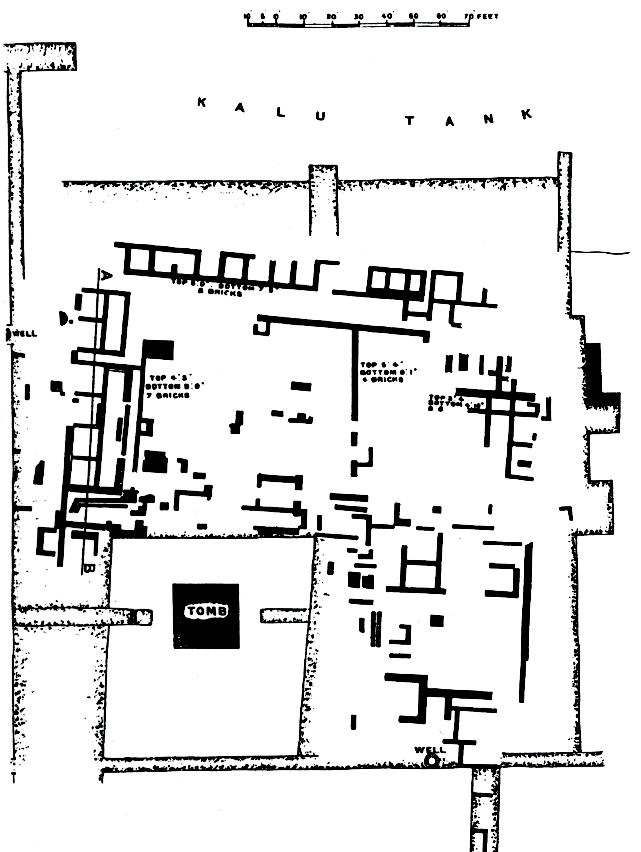

Given the ancient history and antiquity of the city, a series of explorations and excavations were carried out which were started by L.A. Waddell[3] in 1892. Waddell carried out excavations in Patna at various sites such as Bulandi Bagh, Chhoti Pahari, Tulsimandi, Maharajganj, Rampur, Bahadurpur, and Kumhrar. At Kumhrar he discovered a broken Ashokan Pillar. After Waddell, D.B. Spooner of Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) carried out excavations from 1912 to 1916 when remains of brick walls belonging to the Gupta and Post-Gupta period were found at Kumhrar. Below these walls there were fragments of polished sandstone pillars occurring at an interval of 4.57 m or 15 feet. He found 80 pillars in 8 rows and thus concluded that the site of Kumhrar belonged to a Mauryan pillared hall similar to Achaemenid Hall of Persepolis[4]. Thus, the site of Kumhrar came to be known as 80-pillared Assembly Hall of Mauryan Dynasty.

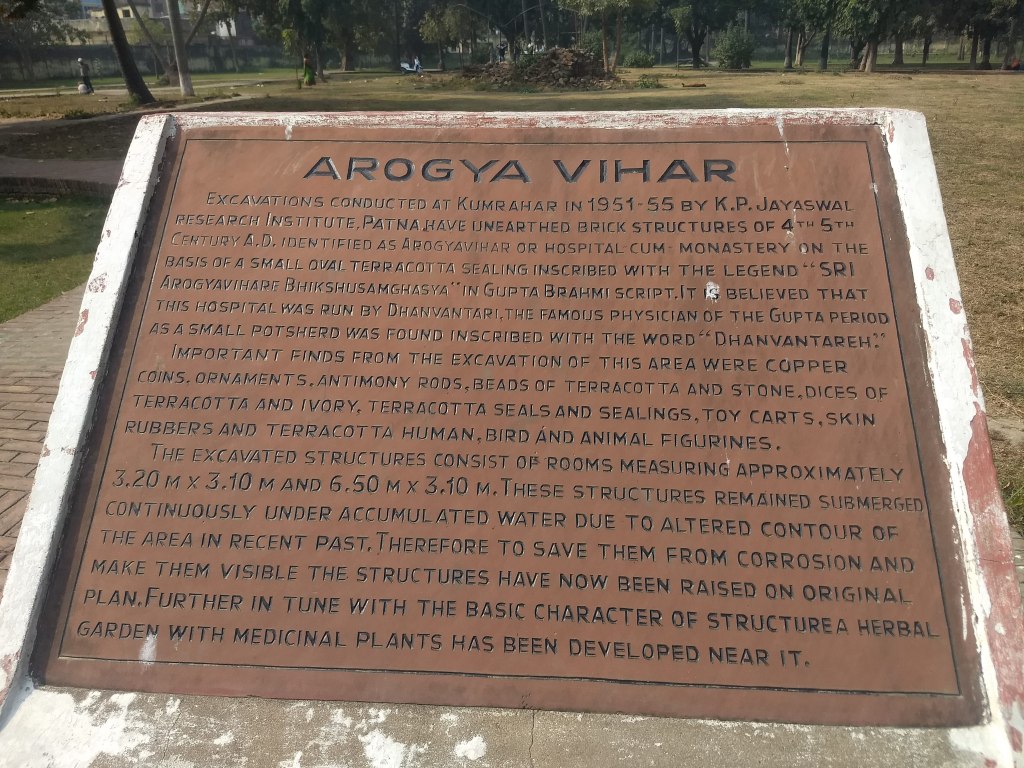

After independence, K.P. Jayaswal Research Institute of Patna undertook the excavations at Kumhrar from 1951 to 1955. In addition to the evidence of pillared hall, structural remains belonging to Buddhist monasteries from 2nd Century BCE to 6th Century CE. Travelogue of Fa-Hien mentions about a structure known as Arogya Vihar which was a monastery-cum-hospital, and a seal uncovered during the excavation confirms the presence of this structure. Several other objects such as coins, seals, terracotta figurines, beads etc were also uncovered which were later dated. Dating of these objects confirmed that the site of Kumhrar was continuously inhabited from Mauryan Period till 600 CE after which it became deserted.

Today, if one visits the site of Kumhrar Park, they will only be able to see the manicured lawns and brick pathways and not the excavated area as all of it has now been covered to safeguard the archaeological site. However, one sandstone pillar of the 80-pillared Assembly Hall has been put on display to show the ingenuity of Mauryan Era. Some of the other artefacts which were obtained during the excavations have been displayed in the museum located inside the park while others have been moved to Patna Museum and Bihar Museum.

It is disheartening for me to mention that even locals are not aware of this historic site partly because of the poor interpretation strategies of the site that I have witnessed till 2019. I have not visited Kumhrar for a while now hence I cannot comment on the present situation but it’s my humble appeal to everyone to visit this historic site at least once, you won’t be disappointed!

[1] Raja Udayin Bhadra was contemporary of Lord Buddha who he is said to have visited the place on his final journey from Nalanda to Kushinagar.

[2] A Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveller, and translator who visited India in 7th Century CE.

[3] He was a military officer in British Indian Army and an explorer.

[4] Achaemenid palaces had enormous hypostyle halls called apadana, which were supported inside by several rows of columns. The Throne Hall or “Hall of a Hundred Columns” at Persepolis, measuring 70 × 70 metres was built by the Achaemenid king Artaxerxes I.

Sources:

- Gupta, V. K., & Mani, B. R. (2019). Pataliputra. The Texts, Political History and Administration till c. 200 BC, 593-598.

- National Informatics Centre. (2024). History of the District. Retrieved from Patna: https://patna.nic.in/history/